The day we saved the alphabet – but may lose the language

The Albanian language is slowly losing its purity and distinct identity—not through force or policy, but through everyday habits and social influence. English and other foreign words are quietly replacing native ones in conversation, media, and culture, showing that the real threat to the language today isn’t external domination, but internal indifference.

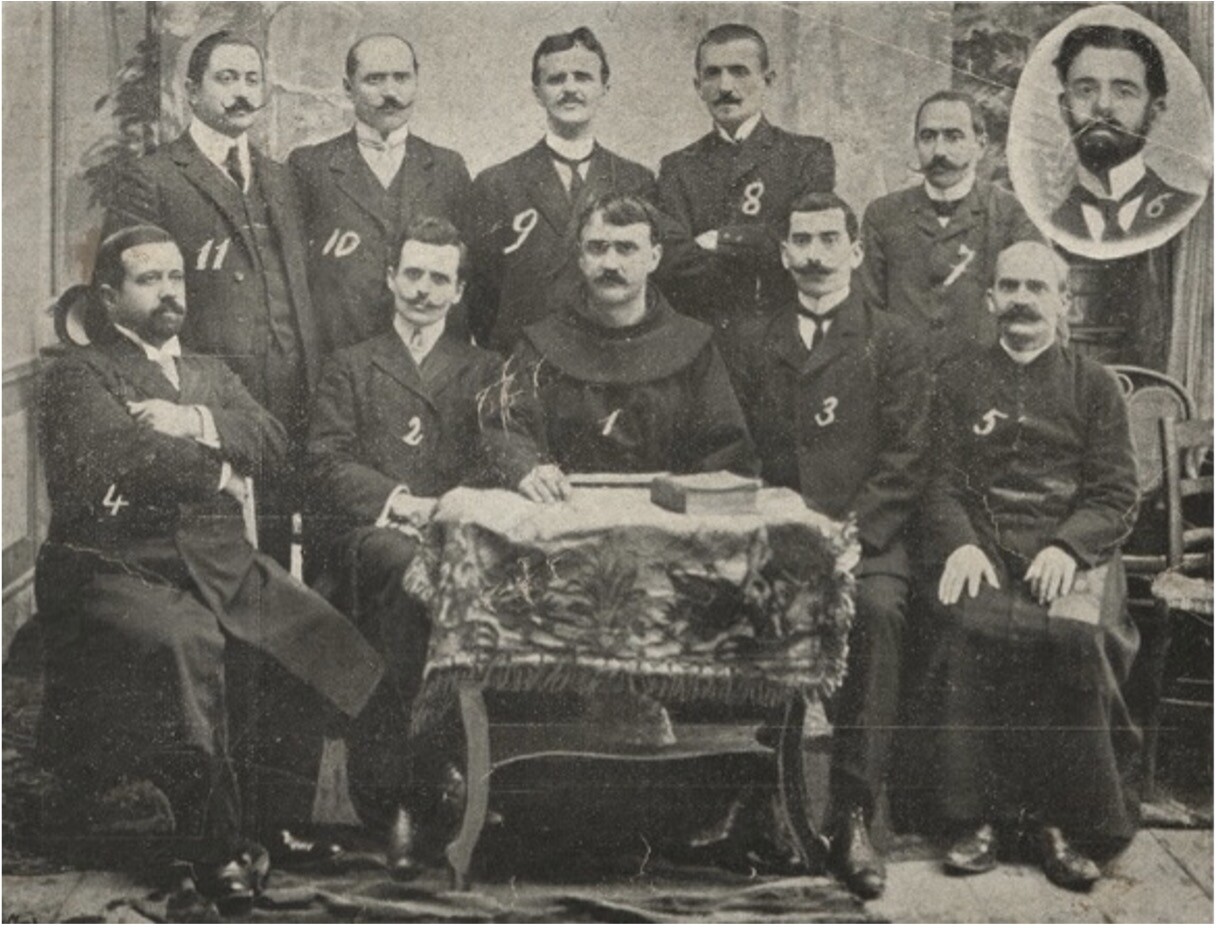

The core commission of the Congress of Manastir comprised by Gjergj Fishta, Mid’hat Frashëri, Luigj Gurakuqi, Gjergj Qiriazi, Dom Ndre Mjeda, Grigor Cilka, Dhimitër Buda, Shahin Kolonja, Sotir Peci, Bajo Topulli, Nyz’het Vrioni

Photo by Kel Marubi, 1908

This morning, while riding the Kamza–Tirana bus line, I overheard two girls chatting about their daily lives. One of them said, “Mirela, have you seen this hot guy on Tinder? Uee, this fella with the SUV looks hot. That’s my type. Give him a scroll anyway.” Later, when I turned on the TV to watch the morning news on Top Channel, the headline read: “TOP STORY: INFLUENCERI I NJOHUR BËN NJË ‘STATEMENT’ QË BËHET VIRAL.”

That’s when it hit me: not only teenagers on the bus, but even mainstream media are blending English words into Albanian sentences. Through these snippets of everyday life, I realized that the Albanian language is slowly losing ground – not through force, but through social contagion. Words like live, trend, breaking news, VIP, statement, overview, deçiziv, siguracion, scroll, and type are replacing their Albanian counterparts. It’s happening quietly, almost invisibly – each borrowed word pushing an Albanian one closer to extinction.

This reflection comes at a meaningful moment in our linguistic history: Alphabet Day. From the 1908 Manastir Congress that unified our alphabet, to the modern habits that weaken our language daily, we are witnessing how a language once defended with sacrifice now fades—not from invasion, but from indifference.

A Short History of the Albanian Language

The Albanian language (gjuha shqipe) is among the oldest in the Indo-European family, with roots often traced to ancient Illyrian origins. It has two main dialects: Gheg in the north and Tosk in the south. While no written Illyrian texts survive, many words – like yll (star), thikë (knife), dele (sheep), dashi (ram), ujk (wolf) – and city names such as Durrës and Tirana, reveal clear linguistic continuity.

The earliest written reference to Albanian dates to 1284, in a letter from the Republic of Ragusa, while the oldest known Albanian text is “Formula e Pagëzimit” (The Baptism Formula, 1462) by Archbishop Pal Engjëlli.

Through centuries of Ottoman rule, Albanian absorbed influences from Greek, Latin, Slavic, Arabic, and Turkish. Yet it persisted. Works like Meshari (1555) and Çeta e Profetëve (1685) preserved it. The 19th-century National Awakening elevated language unification as a patriotic cause, culminating in the Manastir Congress (1908), which standardized the Albanian alphabet using Latin characters.

After independence in 1912, efforts to study and protect the language intensified – reaching another milestone with the 1973 Grammar Congress, which solidified its rules. Today, Albanian boasts a written record spanning more than six centuries.

Silent Threats in the Modern Era

After the fall of communism in 1991, Albania opened its doors to the world. Global media, pop culture, technology, and migration brought new words – and slowly replaced old ones. Dictionaries such as Fjalori i Gjuhës Shqipe (2008) and Fjalori Etimologjik Shqiptar (2018) sought to preserve vocabulary, but habits changed faster than books could keep up.

Now, the threat doesn’t come from censors or invaders – but from comfort. From the teenager mixing English and Albanian (scroll, live, slay, hashtag), to journalists favoring “international” over “ndërkombëtar”, or “brand” over “markë.” Even city names are often written incorrectly instead of adapted to Albanian: New York – Jorku i Ri; Washington – Uashingtoni; Los Angeles – Los Anxhelosi; Venezia – Venecia.

Every borrowed word may feel harmless, but collectively, they blur the edges of our identity. The language that survived centuries of occupation now faces a quieter enemy: our own indifference.

How Albanian Influenced Others

Foreign scholars often describe Albanian as a language filled with borrowed words – but this misses the full story. Albanian has given as much as it has borrowed.

Greek includes μπέσα (besa), meaning “word of honor,” directly from Albanian. Slavic dialects use bašk (exactly) and kajmak (cream), believed to originate from Albanian pastoral terms. Place names across Montenegro, Kosovo, and southern Serbia carry pre-Albanian or Albanian roots – proof of an enduring linguistic footprint.

Albanian isn’t just surviving – it has shaped the linguistic landscape of the Balkans for centuries.

Before We Lose Them: Simple Alternatives

Languages fade not through prohibition, but through small, everyday choices. Here are a few quick swaps that help keep Albanian strong:

| Foreign Word | Albanian Equivalent |

|---|---|

| application/app | program |

| brand | markë |

| breaking news | lajmi i fundit |

| copyright | e drejtë autori |

| download | shkarko |

| event | ngjarje |

| file | skedar |

| influencer | ndikues |

| live | drejtpërdrejt |

| network | rrjet |

| scroll | lëviz poshtë/lart |

| statement | deklaratë |

| type | lloj |

| update | përditësim |

| VIP | person i njohur / i rëndësishëm |

| website | faqe interneti |

| weekend | fundjavë |

Each word we choose matters. Language isn’t lost in a day—it fades in conversation, in headlines, in habit.

A Call for Awareness

The Albanian language has survived empires, bans, and centuries of pressure. Its greatest threat today is neither political nor external—it’s quiet, internal, and cultural.

Every time we choose a foreign word for style or convenience, we erode a bit of our linguistic foundation. The change isn’t dramatic—it’s gradual, like color fading from a photograph. A teenager saying scroll, a journalist writing breaking news, a billboard promoting a brand—none of these seem alarming, but together, they reshape our language.

This is not a plea for isolation. Borrowing enriches a language when done thoughtfully. But when drejtpërdrejt becomes live out of laziness, when përditësim turns into update out of habit, that enrichment turns to erosion.

The responsibility lies with all of us—schools, media, institutions, and everyday speakers. Preserving Albanian doesn’t require grand gestures—just awareness. Choosing the native word when it exists. Writing place names correctly. Encouraging young people to value the words that carry our stories. Albanian has given us identity, poetry, and unity. Now it asks for something simple in return: use it.