Mujo Ulqinaku: The first anti-fascist hero of the world?

Mujo Ulqinaku is remembered as one of the first anti-fascist heroes of the 20th century, not only in Albania, but also beyond, being remembered as one of the first symbols of global resistance against fascism.

Introduction

Mujo Ulqinaku is remembered as one of the earliest anti-Fascist heroes of the 20th century, not only in Albania but also in the broader context of global resistance against Fascism. His bravery during the Italian invasion of Albania on April 7, 1939, places him alongside those who stood against oppression in countries like Ethiopia, Spain, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. Revered in Albanian history, his name has been memorialized in schools, streets, monuments, and history books—though his legacy has often been shaped and, at times, distorted by the ideological narratives of Communist Albania.

From the Kingdom of Albania through its occupation and into the decades of dictatorship and beyond, Ulqinaku’s story reflects the broader struggles of a small nation caught in the storm of European totalitarianism. His resistance in Durrës, though short-lived, was symbolically powerful. It not only demonstrated individual heroism but also exposed to the world the brutal nature of Fascist aggression. This concise article explores the life, legacy, and lasting symbolism of Mujo Ulqinaku across different historical periods in Albanian memory and historiography.

Biography: The Introduction of Mujo Ulqinaku

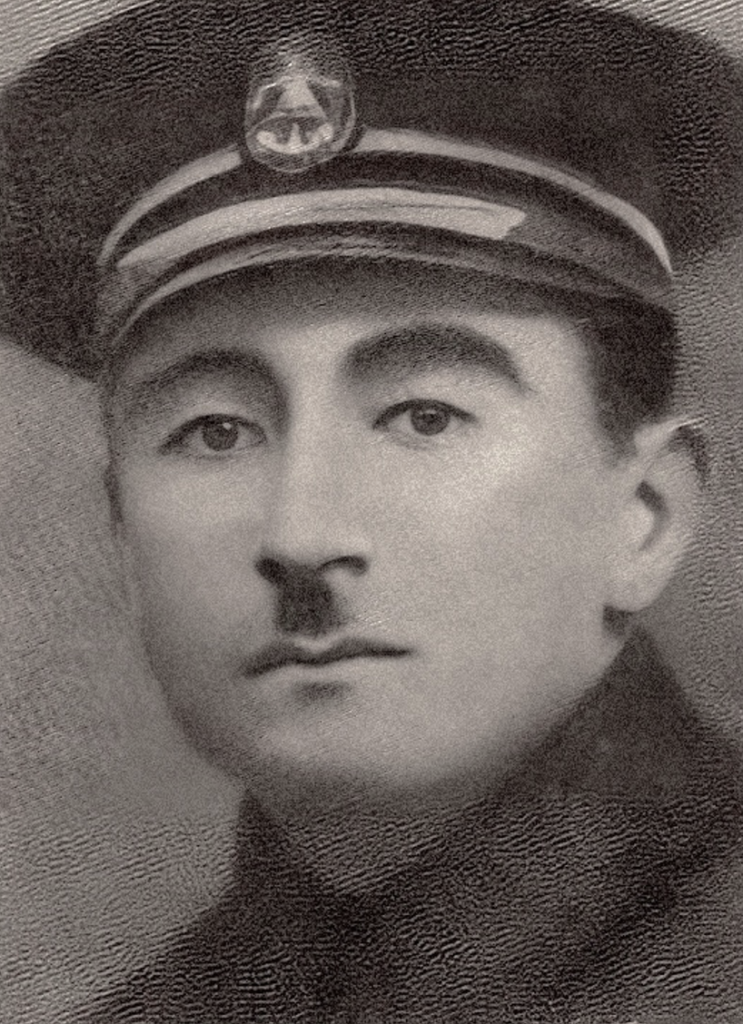

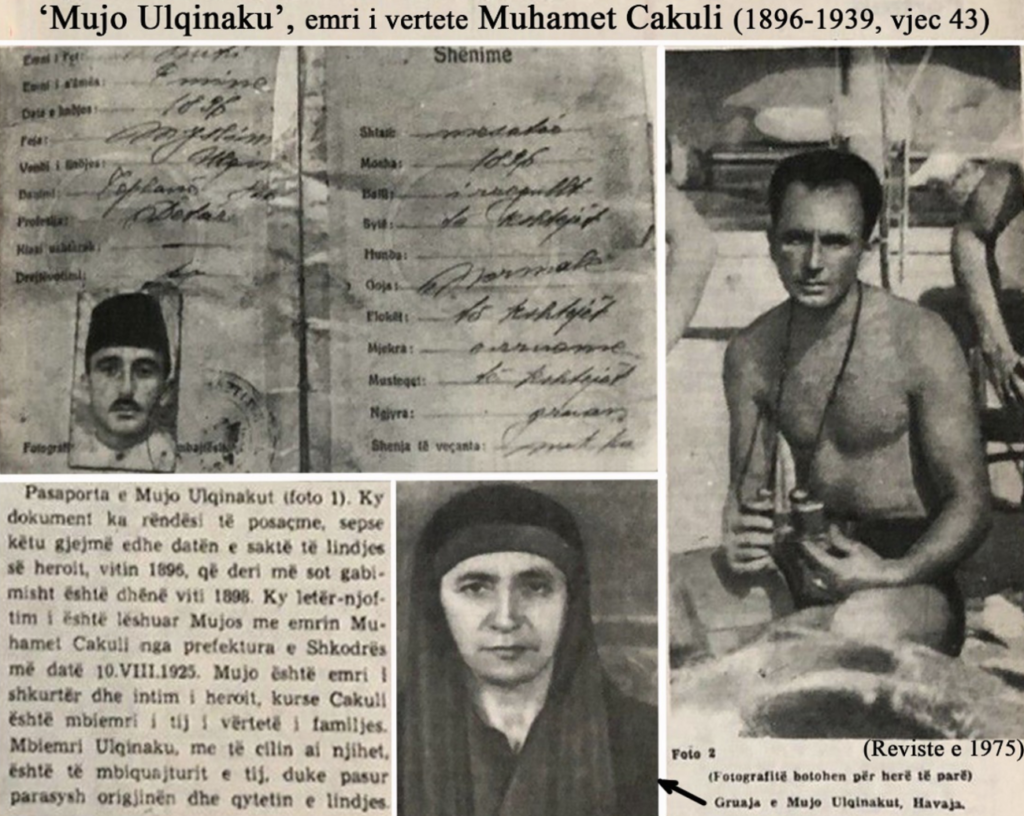

Mujo Ulqinaku, also known as Mujo or Muhamet Cakuli, was born in 1896 in Ulqin, an Albanian town located about 40 kilometers from Shkodra. He came from a well-known family, and his hometown of Ulqin held a prominent role as a key base for the Albanian navy and maritime activities, including sea piracy. Following the annexation of Ulqin and its surrounding region by Montenegro in 1880, as determined by the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Cakuli family was forced to leave their homeland. They first relocated to Shkodër and later settled in Durrës.

According to a Communist Albanian chronicle of „Kinostudioja: Shqipëria e Re“(Studio Films: New Albania) titled „Lufton Djali, lufton Plaku, lufton Mujo Ulqinaku“ (“The Boy Fights, The Old Man Fights, Mujo Ulqinaku Fights”), Marubi was known for the first photoshoot of Mujo Ulqinaku as a fisherman in Shkoder. In the end of 1920s, he was trained in Italy and specialized in the captain of Albanian Marina in Shkodër first, then later in Durrës.

Meantime in Albania…

Since the Vlora War of 1920 and the last decisions of Paris Peace Conference of 1919-1921, Italy was obliged to retreat from the country, apart from Sazan Island and to be one of the protector countries of Albania. Five years later, Ahmet Zogu, an ex-Albanian patriot and deputy of Conservative Party, after taking power, he thought on how to rely on economic and social support between Yugoslavia, Greece, and Italy.

Due to the Italian pressure, Zogu was forced to rely on Italy, to buy financial credits to finance ist army, develop the social life of Albania, and expand the main cities of Albania, mainly Durres and Tirana. Since this situation was worsened in Albania after the marriage of Zogu with Queen Geraldine of Hungary and Zogu’s alliance with Nazi Germany, the rival of Fascist Italy, Ciano and Mussolini decided to start a war against Albania, by sabotaging the army, locking the weaponry storage, and stopping in financing into the Albanian economy.

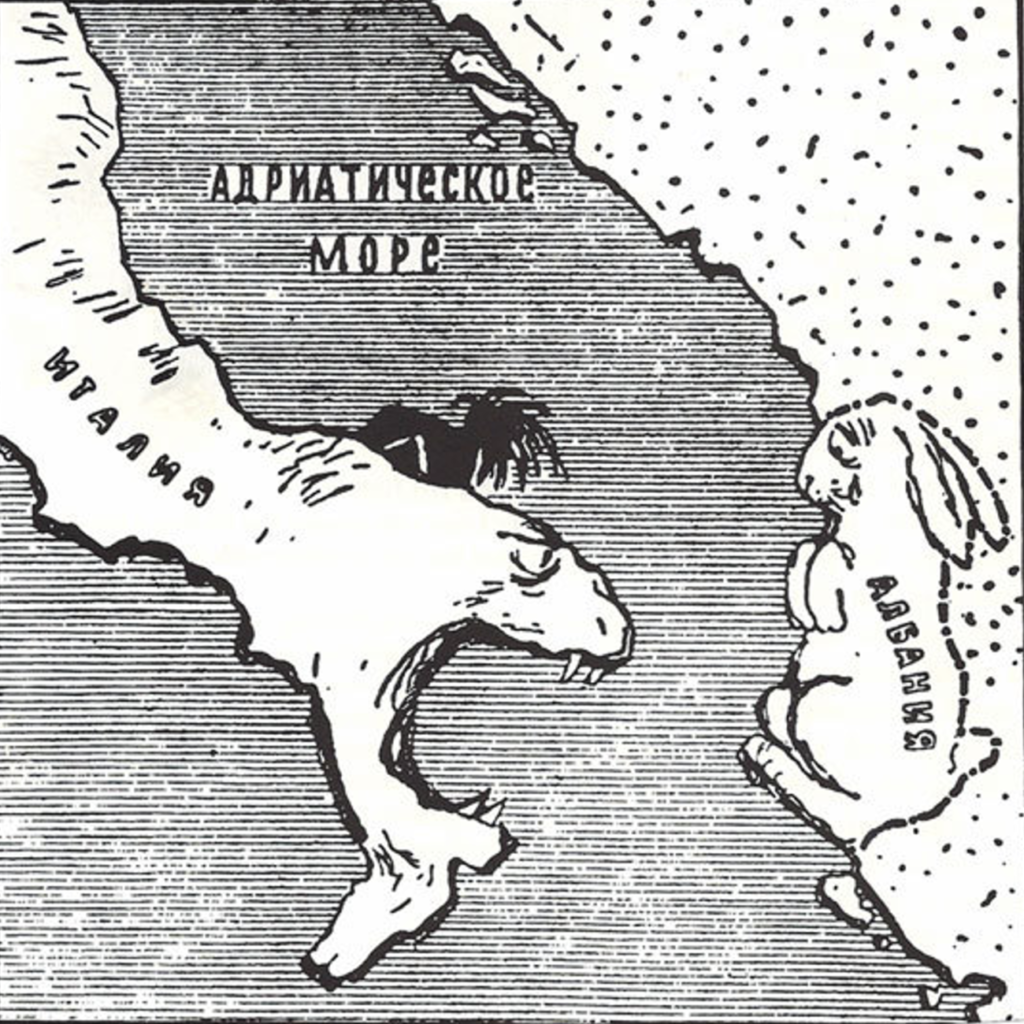

Moreover, Italian pressure on Albania stemmed from Italy’s imperialist ambitions to dominate the Mediterranean region and parts of Africa. The Secret Treaty of London (1915) promised Italy significant territorial gains in Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, and Turkey. This fueled the aspirations of Italian nationalist politicians, who began to envision a redrawn map of Italy that included expansion into these regions. One of the main proponents of this vision was Benito Mussolini, widely known as Il Duce. After coming to power in Rome in 1922, Mussolini actively pursued plans to expand Italian influence over Albania’s internal affairs.

Although Ahmet Zogu made efforts to protest Italy’s foreign policy in the Balkans by appealing to French, British, American, German, Yugoslav, and Greek authorities, his warnings went unheeded. The decision to occupy Albania had already been made. The invasion was scheduled for Easter Sunday—known as the “Black Sunday”—with a plan to deploy 50,000 Italian troops to occupy the country within 48 hours. The operation, code-named OMT (Oltre Mare Tirana – “Across the Sea to Tirana”), envisioned a swift takeover, the abolition of Zogu’s monarchy, the establishment of an Italian Protectorate in Albania, and the eventual unification of Albanian-speaking territories from Yugoslavia and Greece under Italian control.

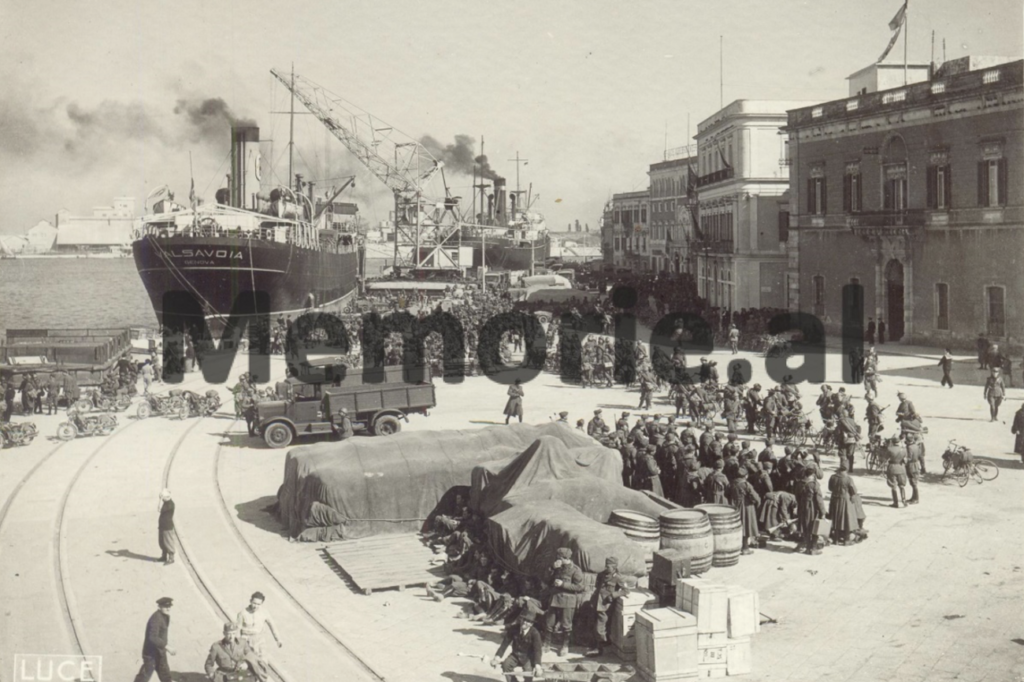

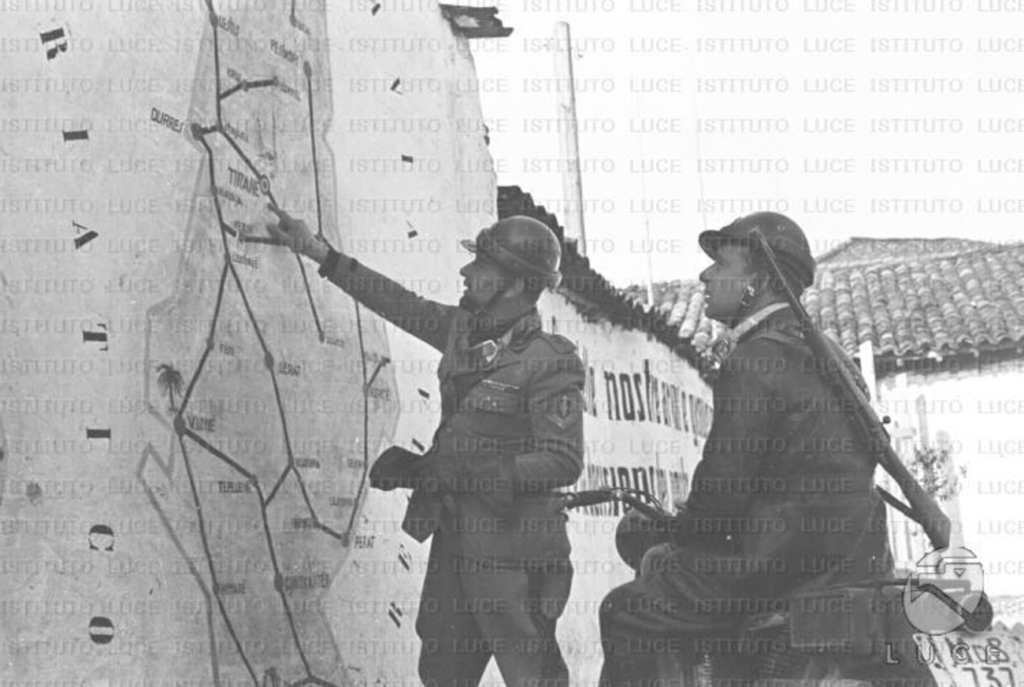

Durres in the Black Sunday

On April 7th, 1939, at 5:00 AM, Italian forces led by Generals Alfredo Guzzoni and Alberto Pariani launched a coordinated invasion of Albania, targeting four main ports: Shëngjin, Durrës, Vlorë, and Sarandë. Although the Italian authorities attempted to mask the aggression through propaganda films produced by the Istituto Luce, the reality on the ground was far different. Reports of armed resistance were confirmed by British military officers, the U.S. Ambassador Hugh S. Grant, and telegrams sent by the Albanian Army and Gendarmerie from the invaded ports to Tirana, detailing the unfolding conflict.

For example, Abaz Kupi, the commander of Durres County division telegrammed:

The Italian fleet has surrounded Durrës and entered the Port. There are more than 30 ships in Durrës, Porto Romano, and the Baths area (Durrës Beach). We didn’t have time to mine the port. We will do our duty, but the aviation is causing us a lot of damage. Order the command in Shijak to come to our aid, especially to secure the Baths area (Durrës Beach).

The battle in Durrës lasted for approximately six hours, during which around 150 Albanians lost their lives. Among them was Mujo Ulqinaku, who was reportedly killed either by an Italian naval shell or a rifle bullet while stationed at the Venetian Tower of Durrës. On the opposing side, roughly 400 Italian soldiers were killed between April 7th and April 14th. The final phase of the invasion occurred with the occupation of Kukës, the last Albanian city to fall, which Italian propaganda films from the Istituto Luce portrayed as a peaceful welcome by the local population and authorities. Although General Guzzoni had promised Mussolini that Albania would be conquered in just 48 hours, the operation ultimately took 168 hours.

The fate of Mujo Ulqinaku’s body remains unverified. Due to his rank, reputation, and heroic role, it is widely believed that he was buried with honors by the people of Durrës. His story has been preserved primarily through the work of Moikom Zeqo, a fellow native of the Adriatic coastal region where the 1939 conflict unfolded. In a 2019 interview, Zeqo recounted that during a 1949 visit to Albania—ten years after Ulqinaku’s death—the renowned French poet Paul Éluard expressed disbelief in the tale of Mujo Ulqinaku.

Following the landing of Italian troops in Durrës, resistance continued to flare across the country. In the southern and northern ports of Saranda, Vlorë, and Shëngjin, Albanian forces and civilians engaged in day-long battles to prevent the Italians from advancing inland toward strategic cities like Shkodër, Fier, and Gjirokastër. Despite being outnumbered and underequipped, local resistance groups managed to delay the occupation and stir unrest throughout the territory. Over the following month, anti-Fascist sentiment intensified. The Italian-appointed governor began implementing aggressive policies of Italianization—imposing the Italian language, attempting to fuse the Albanian double-headed eagle with Fascist emblems, and enforcing political loyalty to Rome. These actions only deepened public resentment and gave rise to the early stages of organized anti-Fascist resistance in Albania.

The invasion also had wider geopolitical implications. Greece, Albania’s southern neighbor, used the Italian occupation as a pretext to pursue its long-standing territorial claims over the region known as “Northern Epirus,” which includes Gjirokastër and Korçë. Greek nationalist and military circles accused Albania of aligning with the Axis powers—Fascist Italy, Imperial Japan, and Nazi Germany—and particularly targeted the Muslim Albanian population in Çamëria, branding them as collaborators. This narrative was used to justify Greece’s declaration of the Law of War against Albania, a legal state that, remarkably, remains technically in place even 85 years later.

Its northern neighbor, Yugoslavia, was afraid of the Italianization of Balkans and started to militarize its country and put pressure towards the Albanian community in Yugoslavia. In addition to the Greek and Yugoslav justifications, Bulgaria, another country in the Balkans, also used the Italian occupation as a justification to aim at protecting the Bulgarian minority in Albania and as a threat against the influence of Sofia. This stance was also supported by the wife of King Boris III, queen Giovanna of Savoy Royal House, who had Italian origins.

Nonetheless, Albania’s response to Fascist aggression did not go unnoticed internationally. The Daily Telegraph remarked in a prominent subtitle that Albania was among the few nations in Europe that actively resisted Fascist occupation from the outset, contrasting its stance with that of Austria and Czechoslovakia, which had fallen to Hitler with far less resistance. This legacy of defiance, despite Albania’s small size and limited resources, has remained a defining chapter in its modern history.

Ulqinaku in Communist Albania and Later Depiction

After the establishment of Communist Albania in 1944, Enver Hoxha covered the Italian Invasion of Albania with many propagandas. According to their propaganda in the history books of Albania, it is cited that Mujo Ulqinaku, altogether with Haxhi Tabaku, Hamit Dollani were members of different Communist Albanian groups. However, after 1990s, it was never proven that the main characters of that day proved any sympathy for communism in Albania. Furthermore, Zogu’s regime was known during its regime as anti-popular or Fascist regime of Zogu, in whom, he never collaborated with Fascism.

In 1970’s, roads, statues, movies, and songs were dedicated to Mujo Ulqinaku and its heroism in Albania. However, a part of his family was persecuted. His son, Hamit Ulqinaku got famous as his dad, by being a pilot in the Albanian Air Fleet, but later after a scandal, he was never shown by the Albanian authorities for 10 years, under the pressure of the Albanian Secret Services. Furthermore, his friends, who survived from the warfare of Durres in 1939, survived their lives in the prisons of Communist Albania. Meanwhile, Abaz Kupi, after he experienced a big failure in the organization of his anti-communist group in World War II, escaped to Italy, then to the United States, where he died in 1976, while his family was persecuted by Fascist and Communist regimes.

During his regime, Enver Hoxha sought to portray himself as a participant in the anti-Fascist resistance of April 7, 1939. He claimed that he had volunteered to travel from Korçë to Durrës with a group of students from the French Lyceum of Korçë to resist the Italian invasion. However, historical evidence suggests these claims were unfounded. In fact, early in the occupation, Hoxha is known to have cooperated with the Fascist authorities, who covered his medical expenses and financed his treatment in Italy. He was reportedly both shocked and pleased to witness the Albanian Royal Family’s departure from Korçë to Greece—an event that foreshadowed his own unexpected rise to power just five years later, when he would become Albania’s prime minister and rule the country for the next 45 years.

In recent years, Albanian journalists and historians such as Blendi Fevziu, Marenglen Kasmi, Marin Mema, and Mishel Koçiu have worked to shed light on the true story of Mujo Ulqinaku and his courageous stand against the Italian invasion, while also highlighting the perceived cowardice of King Zog in the face of Mussolini’s imperial ambitions. Despite these efforts in the media, the Albanian government once controversially awarded Galeazzo Ciano—the Fascist Italian foreign minister and Mussolini’s son-in-law—the title of Honorary Citizen of Albania. This symbolic act stands in stark contrast to the sacrifices of national heroes like Mujo Ulqinaku and appears to undermine their legacy. As time passes and official narratives shift, Ulqinaku’s story risks fading into obscurity, becoming a distant memory for the public and treated with indifference by much of Albanian society.

Conclusion

Mujo Ulqinaku stands as one of the earliest symbols of resistance not only in Albania but also in the broader fight against Fascism across Europe. His courageous stand against overwhelming Italian forces during the invasion of April 7, 1939, earned him a lasting place in Albanian national memory. Though his life was cut short during the first hours of battle in Durrës, his sacrifice ignited a sense of defiance that resonated beyond his lifetime, inspiring future generations to value freedom and national sovereignty.

His legacy was preserved, albeit reshaped, by Communist Albania, which used his name and actions to bolster its own narratives of resistance and patriotism. Streets, schools, and statues were named after him, but behind the glorification, many aspects of his true personal history—including the persecution of his family and the complexities of the time—were either ignored or revised to fit political agendas. Nevertheless, Mujo Ulqinaku’s heroism transcends ideology. He remains a figure of dignity, bravery, and sacrifice who chose to resist an imperialist force rather than surrender.

Today, his story is a poignant reminder of the importance of standing against oppression, even when the odds seem impossible. His name endures not just as part of historical record, but as part of a living memory of Albanian identity and resistance.